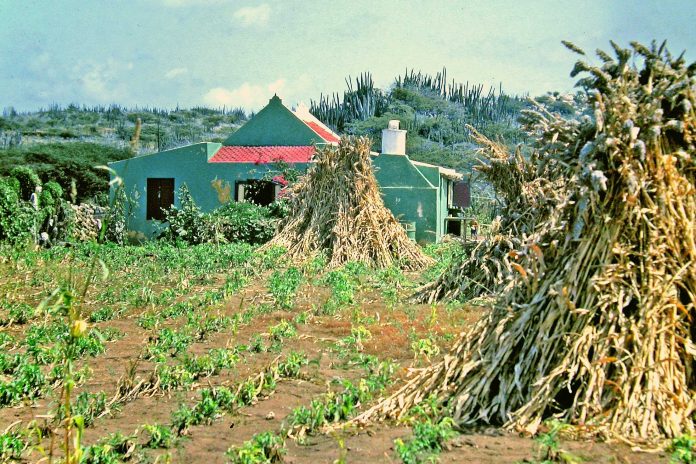

(Oranjestad)—Aruba’s culture consists of rich historical traditions that make up the Aruban identity and lifestyle. However, the life of the cunukero (farmer) is perhaps the most important aspect of our culture, in a sense representing to locals the true essence of the Aruban.

Historically, cunucus (farms) played a huge role in the early social and economic development of Aruba, and its relevance dates back to the early days of the colonization era. Upon being discovered by Spanish conquistadors in the late 15th century, Aruba was used primarily as a ranch, housing horses and cattle brought from Europe. During the Dutch colonization era where the West Indian Company (WIC) dominated the economic sphere on the island, using the land to set up cattle farms and ranches remained popular.

Anthropologist Sidney Mintz divided Caribbean farmers back in four categories:

- The “squatters”, who were mostly comprised of illegal and poor colonists, runaway slaves and deserters who took advantage of the Spanish’s weak supervision on Caribbean islands like Cuba and the DR;

- Then you have “Early Yeomen”, who were legal farmers who came to the west under contract. Once their contract expired, they were given a plot of land for independent use;

- Proto-Peasants were plantation slaves who were allowed to have a small piece of land to grow food for their own consumption. This was to curb the cost of living on the plantations;

- Lastly you have the “Runaway Peasantries”, usually comprised of runaway slaves who acquired farming tools and cattle through stealing or through secret exchanges with other slaves from different plantations.

However, the Aruban cunukeros back then are hard to place, and their history may explain why.

From 1636 (beginning of Dutch colonization era) to before the oil industry in 1924, Aruba’s population consisted of mostly farmers. These farmers were mostly indigenous and were characterized as peasants. They weren’t allowed to participate in trading, but instead were granted a piece of land to live off of. However, in exchange for this grant, these indigenous farmers were obligated to work for the WIC, doing daily tasks such as taking care of or hunting cattle—large majority of which were destined for Curacao, clean water tanks and chop wood, among other things.

As much as these farmers were given to opportunity to live “free” with a plot of land, their exclusion from the trading and business world, as well as being deprived the chance to become real property and cattle owners, made them a unique group among Caribbean farmers at the time.

The WIC placed a lot of restrictions on these indigenous farmers—a method to safeguard their cattle deposit on the island. The indigenous farmers were mostly granted less than 7 acres of land. Those who owned bigger land were either once affiliated with the WIC or were colonists who settled on the island to try their luck at farming. In 1767, there were about 120 houses/cunucus on the island.

These Aruban farmers were also limited to the amount of cattle they could keep. Most kept goats as cattle, as only those who were affiliated with the WIC could keep (more) sheep. Of the 76 goat herders on the island, about 45 of them had less than 30 goats, and only 7 of them had more than 60 goats.

It wasn’t until the WIC was defunct in late 18th century that these farmers were able to obtain more freedom as cunukeros. After 1824, the government gave these farmers official permission to keep livestock, and the obligations once placed on them were officially discarded.

Because of the dry climate in Aruba, growing food for commercial purposes was not popular. The focus was mainly on cattle herding and taking care of livestock. However, livestock need food to survive, and when Aruba experienced its duper dry climate, many farmers would see a big loss in their livestock, and hence profit.

Although the WIC at one point did try to come up with an initiative to get more people to have land on the island, the climate never really allowed real profit from farming. Because of the climate, Aruban farmers in general could not keep large quantities of livestock. At a certain point toward the end of the 18th century, the climate got so bad that many farmers decided to leave the island for a while.

For this reason, the farming economy on the island remained small. As the years went by and people noticed that these farms could not really produce any sustainable profit, farmers kept their small piece of land just to live off of. This is why the Aruban cunukeros only played a very tiny role into the plantation economy.

In modern Aruba, cunucus and cunukeros still exist on the island, fortunately with more freedom and more opportunity to tap into the agricultural market. These farmers usually sell their produce on a smaller scale, like during farmers’ market events and other types of (holiday) events.

Source: “Arubaans Akkoord: Opstellen over Aruba van voor de komst van de olieindustrie (Aruban Accord: Essays on Aruba Before the Arrival of the Oil Industry)” by Alofs, Luc; Rutgers, Wim; Coomans, Henny E. red.