By Michael Casey and Michelle Liu

COLUMBIA, S.C. (AP) — Six months after Congress approved spending tens of billions of dollars to bail out renters facing eviction, South Carolina was just reaching its first tenants. All nine of them.

Like most states, it had plenty of money to distribute — $272 million. But it had handed out just over $36,000 by June. The pace has since intensified, but South Carolina still has only distributed $15.5 million in rent and utility payments as of Aug. 20, or about 6% of its funds.

“People are strangling on the red tape,” said Sandy Gillis, executive director of the Hilton Head Deep Well Project, which stopped referring tenants to the program and started paying overdue rent through its own private funds instead.

The struggles in South Carolina are emblematic of a program launched at the beginning of the year with the promise of solving the pandemic eviction crisis, only to fall victim in many states to bureaucratic hurdles, political inertia and unclear guidance at the federal level.

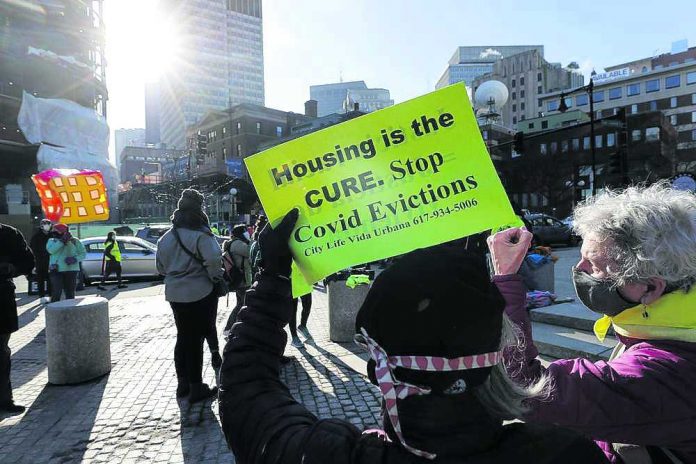

The concerns about the slow pace intensified Thursday, after the Supreme Court blocked the Biden administration from enforcing a temporary ban that was put in place because of the coronavirus pandemic. Some 3.5 million people in the U.S. as of Aug. 16 said they face eviction in the next two months, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

“The Supreme Court decision undermines historic efforts by Congress and the White House to ensure housing stability during the pandemic,” Diane Yentel, CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, said in a statement.

“State and local governments are working to improve programs to distribute emergency rental assistance to those in need, but they need more time; the Supreme Court’s decision will lead to many renters, predominantly people of color, losing their homes before the assistance can reach them.”

The Treasury Department said this week that just over $5.1 billion of the estimated $46.5 billion in federal rental assistance — only 11% — has been distributed by states and localities through July. This includes some $3 billion handed out by the end of June and another $1.5 billion by May 31.

Nearly a million households have been served and 70 places have gotten at least half their money out, including several states, among them Virginia and Texas, according to Treasury. New York, which hadn’t distributed anything through May, has now distributed more than $156 million.

But there are 16 states, according to the latest data, that had distributed less than 5% and nine that spent less than 3%. Most, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, are red states, often with tough-to-reach rural populations. Besides South Carolina, they include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Florida, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Mississippi and New Mexico.

There are myriad reasons for the slow distribution, according to the group. Among them is the historic amount of money — more than the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual budget — which required some 450 localities to create programs from scratch. Getting the money out is also complicated by the fact that checks aren’t sent directly to beneficiaries like, for example, the child tax credit.

States and localities have also struggled with technology and staffing, as well as reaching tenants without access to the internet, or small landlords unaware of the help. Some have applications so complicated they scare off prospective applicants or have income documentation and pandemic impact requirements that can be time-consuming.

Efforts to use coronavirus relief money for rental assistance last year faced similar challenges.

“A lot of states are lagging behind,” said Emma Foley, a research analyst with the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “The fact that this many states still have distributed so little is worrisome.”

In South Carolina, lawmakers were slow to roll out the state’s program, waiting until April to charge the state housing authority with distributing the money. It took weeks to set up its program, with the first help not going out until June.

Housing advocates have also criticized the reams of documentation required and the months of waiting for tenants to find out whether they qualify.

Shaquarryah Fraiser applied in May and is still waiting to hear whether she will get help paying months of back rent for the mobile home she rented with her mother for $550 a month in Sumter, South Carolina. Fraiser’s mother died of COVID-19 last year, and the 29-year-old fell behind after getting sick herself with pneumonia and losing her phone survey job.

“It’ll take a lot of stress off of me. I won’t be so anxious about this situation,” said Fraiser of the prospect of getting the help.