The narrative of Etnia Nativa highlights the importance of reclaiming Aruba’s cultural identity and heritage. Through this platform, it shares an authentic native perspective, educates the public, and inspires readers to adopt an “island caretaker” mindset.

Join us and discover how education and literacy have shaped Aruba’s contemporary cultural life.

Day-to-day life in early 19th-century Aruba was largely monotonous. Many people preferred to rest in hammocks, seeking refuge from the scorching sun and oppressive heat. Reading was uncommon—partly due to a long-standing misinterpretation of an old proverb passed down through generations, which warned that “reading can drive people mad.”

At that time, only two schools had been established on the island. The public school offered Protestant education in Dutch, while the Roman Catholic school provided instruction in Spanish. In the late 1800s, nuns gradually took over teaching responsibilities.

Schools were opened in Oranjestad, Noord, and Santa Cruz. In Oranjestad, Dutch was the only language of instruction in both public and Catholic schools. In contrast, schools in Noord and Santa Cruz began to replace Spanish with Papiamento—the local language. By the turn of the century, a school in Savaneta was also teaching in Papiamento. Meanwhile, a small Protestant school was founded in Piedra Plat, located northeast of the Hoiberg hill.

Although Aruba did not experience significant economic or demographic growth during this period, islanders generally lived content and peaceful lives.

With the exception of folk dances, religious ceremonies, and harvest festivals—some of which were documented in Van Meeteren’s Volkskunde (Ethnology)—very little historical literature captures the island’s early cultural evolution. However, Hartog’s writings mention Aruba’s first native Antillean poet, “Mosa Lampe,” who reportedly wrote letters in Dutch and enjoyed composing and reading Dutch poetry.

In 1894, the Arubasche Courant (Aruban Newspaper) was founded. As the century progressed, reading gradually became more widespread, although access to formal education remained limited.

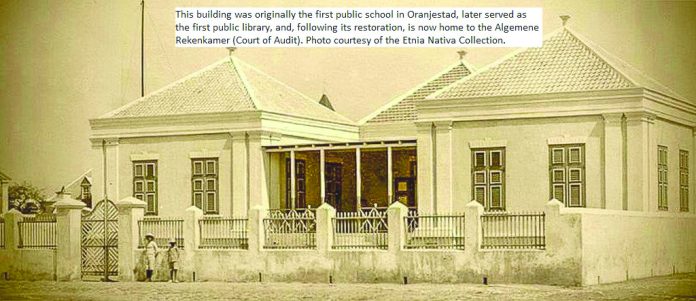

In 1905, a library was established in Aruba. Initially serving only 12 members, it functioned as a subsection of the Curaçao Library, which was part of the Netherlands Antilles branch of the Algemeen Nederlands Verbond (Universal Dutch Association). The city of Rotterdam contributed nearly 500 books to the library’s founding collection.

The arrival of the oil industry in 1924—with companies like Eagle and Lago Petroleum Corporation—had a significant impact on education and vocational training. The Lago Oil Company launched a top-of-the-line apprenticeship program to teach young men English, mechanical and technical skills, preparing them to work at what was then the world’s most modern oil refinery. Aruba’s first trade school was officially established in 1952.

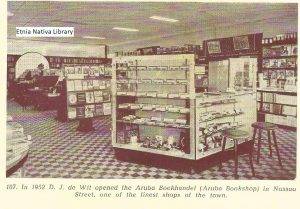

In terms of literary culture, the Aruba Boekhandel (Aruba Bookshop) began as a single small business in the 1950s. It eventually expanded into a company operating five separate shops. Unlike bookstores in the Netherlands, Aruba’s bookshops also sold toys and other non-literary items, which helped attract customers and boost book sales. Within ten years, book turnover had increased to nearly four times what it had been in 1950.

Magazines—primarily imported from the United States—had a monthly circulation of approximately 30,000 copies. While this might suggest that English-language publications were more popular than Dutch ones that was not the case. The sale and circulation of Dutch books—particularly through the Public Library—consistently exceeded those of English titles.

The Public Library experienced significant growth. Initially, it circulated approximately 15,921 books. By the 1960s, that number had risen to over 60,000—more than one book per resident. Around this time, the library moved to a larger building in Oranjestad to accommodate the island’s growing appetite for reading.

This expansion continued into San Nicolas, where a library branch opened to the public in September 1959. It soon developed into a fully functioning public library, with dedicated sections for both adults and children.

Tired of Aruba’s tourist façade? Then it’s time to go deeper. Etnia Nativa isn’t a souvenir shop or staged attraction—it’s the island’s cultural heartbeat. An authentic, ever-evolving space, founded in 1994 by a visionary who helped shape Aruba’s National Park, Archaeological Museum, and local artisan traditions.

Tucked away in the high-rise area, this private cultural sanctuary isn’t on tour maps—and that’s intentional. It’s for those who seek authenticity over convenience.

Think that’s you? Come find out. Experience Etnia Nativa Whats App+297 592 2702 etnianativa03@gmail.com