In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, the harried health officials of Peru faced a quandary. They knew molecular tests for COVID-19 were the best option to detect the virus – yet they didn’t have the labs, the supplies, or the technicians to make them work.

But there was a cheaper alternative — antibody tests, mostly from China, that were flooding the market at a fraction of the price and could deliver a positive or negative result within minutes of a simple fingerstick.

In March, President Martin Vizcarra took the airwaves to announce he’d signed off on a massive purchase of 1.6 million tests – almost all of them for antibodies.

Now, interviews with experts, public purchase orders, import records, government resolutions, patients, and COVID-19 health reports show that the country’s bet on rapid antibody tests went dangerously off course.

Unlike almost every other nation, Peru is relying heavily on rapid antibody blood tests to diagnose active cases – a purpose for which they are not designed. The tests cannot detect early COVID-19 infections, making it hard to quickly identify and isolate the sick. Epidemiologists interviewed by The Associated Press say their misuse is producing a sizable number of false positives and negatives, helping fuel one of the world’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks.

What’s more, a number of the antibody tests purchased for use in Peru have since been rejected by the United States after independent analysis found they did not meet standards for accurately detecting COVID-19.

Today the South American nation has the highest per capita COVID-19 mortality rate of any country across the globe, according to John Hopkins University – and physicians there believe the country’s faulty testing approach is one reason why.

“This was a multi-systemic failure,” said Dr. Víctor Zamora, Peru’s former minister of health. “We should have stopped the rapid tests by now.”

___

As COVID-19 cases popped up across the globe, low- and middle-income nations found themselves in a dilemma.

The World Health Organization was calling on authorities to ramp up testing to prevent the virus from spreading out of control. One particular test – a polymerase chain reaction exam – was deemed the best option. Using a specimen collected from deep in the nose, the test is developed on specialized machines that can detect the genetic material of the virus within days of infection.

If COVID-19 cases are caught early, the sick can be isolated, their contacts traced, and the chain of contagion severed.

Within weeks of the initial outbreak in China, genome sequences for the virus were made available and specialists in Asia and Europe got to work creating their own tests. But in parts of the world like Africa and Latin America, there was no such option. They would have to wait for the tests to become available – and when they did, the incredible demand meant most weren’t able to secure the number they required.

“The collapse of global cooperation and a failure of international solidarity have shoved Africa out of the diagnostics market,” Dr. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa CDC, wrote in Nature magazine in April as the hunt was underway.

Nations that got an early jump start in preparing or had a relatively robust health care system already in place fared best. Two weeks after Colombia identified its first case, the country had 22 private and public laboratories signed up to do PCR testing. Peru, by contrast, relied on just one laboratory capable of 200 tests a day.

For years, Peru has invested a smaller part of its GDP on public health than others in the region. As COVID-19 approached, glaring deficiencies in Peru became evident. There were just 100 ICU beds available for COVID-19 patients, said Dr. Víctor Zamora, who was appointed to lead Peru’s Ministry of Health in March. Corruption scandals had left numerous hospital construction projects on pause. Peru also faced a significant shortage of doctors, forcing the state to embark on a massive hiring campaign.

Even now, months later, Peru’s needs are vastly under met. To date, the country has less than 2,000 ICU beds, compared to over 6,000 in the state of Florida, which has 10 million fewer inhabitants, according to official data.

High levels of poverty and people who depend on daily wages from informal work complicated the government’s efforts to impose a strict quarantine, further challenging Peru’s ability to respond effectively to the virus.

When Zamora arrived, he said the government had already decided molecular tests weren’t a viable option. The nation didn’t have the infrastructure needed to run the tests but also acted too slowly in trying to obtain what little was available on the market.

“Peru didn’t buy in time,” he said. “Everyone in Latin America bought before us – even Cuba.”

Antibody tests – which detect proteins created by the immune system in response to a virus – had numerous drawbacks. They had not been widely tested and their accuracy was in question. If taken too early, most people with the virus test negative. That could lead those infected to think they do not have COVID-19. False positives can be equally perilous, leading people to incorrectly believe they are immune.

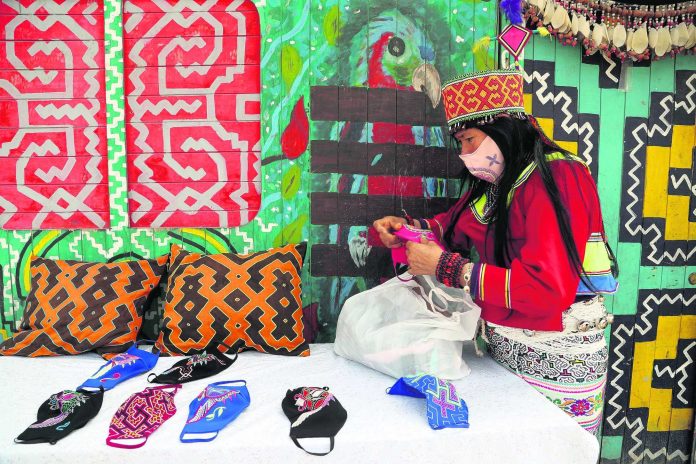

Antibody tests didn’t require high-skill training or even a lab; municipal workers with no medical education could be taught how to administer then.

“For the time we were in, it was the right decision,” Zamora said. “We didn’t know what we know about the virus today.”