As he stood amid the thick old-growth forests in the coastal range of Oregon, Dave Wiens was nervous. Before he trained to shoot his first barred owl, he had never fired a gun.

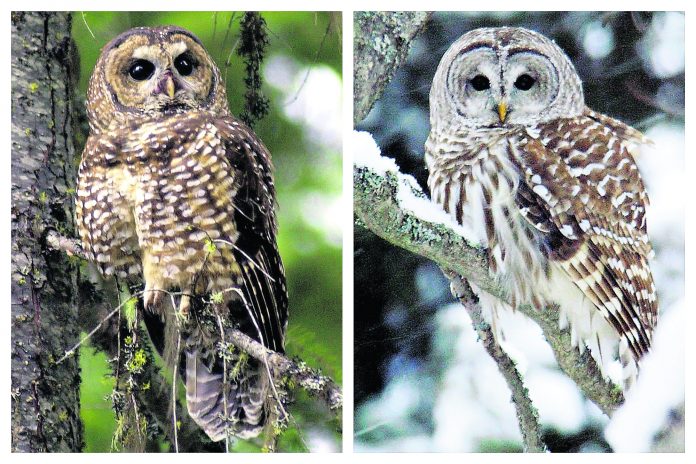

He eyed the big female owl, her feathers streaked brown and white, perched on a branch at just the right distance. Then he squeezed the trigger and the owl fell to the forest floor, adding to a running tally of more than 2,400 barred owls killed so far in a controversial experiment by the U.S. government to test whether the northern spotted owl’s rapid decline in the Pacific Northwest can be stopped by killing its aggressive East Coast cousin.

Wiens grew up fascinated by birds, and his graduate research in owl interactions helped lay the groundwork for this tense moment.

“It’s a little distasteful, I think, to go out killing owls to save another owl species,” said Wiens, a biologist who still views each shooting as “gut-wrenching” as the first. “Nonetheless, I also feel like from a conservation standpoint, our back was up against the wall. We knew that barred owls were outcompeting spotted owls and their populations were going haywire.”

The federal government has been trying for decades to save the northern spotted owl, a native bird that sparked an intense battle over logging across Washington, Oregon and California decades ago.

After the owl was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1990, earning it a cover on Time Magazine, federal officials halted logging on millions of acres of old-growth forests on federal lands to protect the bird’s habitat. But the birds’ population continued to decline.

Meanwhile, researchers, including Wiens, began documenting another threat — larger, more aggressive barred owls competing with spotted owls for food and space and displacing them in some areas.

In almost all ways, the barred owl is the spotted owl’s worst enemy: They reproduce more often, have more babies per year and eat the same prey, like squirrels and wood rats. And they now outnumber spotted owls in many areas of the native bird’s historic range.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s experiment, which began in 2015, has raised thorny questions: To what extent can we reverse declines that have unfolded over decades, often partially due to actions by humans? And as climate change continues to shake up the landscape, how should we intervene?

The experimental killing of barred owls raised such moral dilemmas when it first was proposed in 2012 that the Fish and Wildlife Service took the unusual step of hiring an ethicist to help work through whether it was acceptable and could be done humanely.The owl experiment is unusual because it involves killing one species of owl to save another owl species. But federal and state officials already have intervened with other species. They have broken the necks of thousands of cowbirds to save the warbler, a songbird once on the brink of extinction. To preserve salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest and perch and other fish in the Midwest, agencies kill thousands of large seabirds called double-crested cormorants. And last year, Congress passed a law making it easier for Oregon, Washington, Idaho and American Indian tribes to kill sea lions that gobble imperiled salmon runs in the Columbia River.

In four small study areas in Washington, Oregon and northern California, Wiens and his trained team have been picking off invasive barred owls with 12-gauge shotguns to see whether the native birds return to their nesting habitat once their competitors are gone. Small efforts to remove barred owls in British Columbia and northern California already showed promising results.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has a permit to kill up to 3,600 owls and, if the $5 million program works, could decide to expand its efforts.

Wiens, who works for the U.S. Geological Survey, now views his gun as “a research tool” in humankind’s attempts to maintain biodiversity and rebalance the forest ecosystem. Because the barred owl has few predators in Northwest forests, he sees his team’s role as apex predator, acting as a cap on a population that doesn’t have one.

“Humans, by stepping in and taking that role in nature, we may be able to achieve more biodiversity in the environment, rather than just having barred owls take over and wipe out all the prey species,” he said.

Marc Bekoff, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, finds the practice abhorrent and said humans should find another way to help owl.

“There’s no way to couch it as a good thing if you’re killing one species to save another,” Bekoff said.

And Michael Harris, who directs the wildlife law program for Friends of Animals, thinks the government should focus on what humans are doing to the environment and protect habitats rather than scapegoating barred owls.

“We really have to let these things work themselves out,” Harris said. “It’s going to be very common with climate change. What are we going to do — pick and choose the winners?”

Some see a responsibility to intervene, however, noting that humans are partly to blame for the underlying conditions with activities like logging, which helped lead to the spotted owl’s decline. And others just see a no-win situation.

“A decision not to kill the barred owl is a decision to let the spotted owl go extinct,” said Bob Sallinger, conservation director with the Audubon Society of Portland. “That’s what we have to wrestle with.”

If the experimental removal of barred owls improves the spotted owl populations, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife may consider killing more owls as part of a larger, long-term management strategy. Enough success has been noted that the experiment already has been extended to August 2021.

“I certainly don’t see northern spotted owls going extinct completely,” Wiens said, adding that “extinction in this case will be much longer process and from what we’ve seen from doing these removal experiments, we may be able to slow some of those declines.”q