Destination values, native heritage, and cultural identity are what Etnia Nativa advocates for as its own particular way of safeguarding all reasons to love Aruba. Through this cultural blog, “Island-Insight,” we share awareness, educate, and safeguard native heritage. It is how we encourage you to experiment with an island-keeper state of mind during your stay.

In Aruba, the history of slavery presents itself with a particular situation since the law prohibited indigenous people from being considered “catibo” or captured, and no one had been “brought” from Africa.

Around 1776, the first two names of black slaves became known: Cecilia, a black slave of Bernardino Silvester, and Apolinar, a black slave of Jacob Alvarez. Silvester and Alvarez were two families from Alto Vista-Noord.

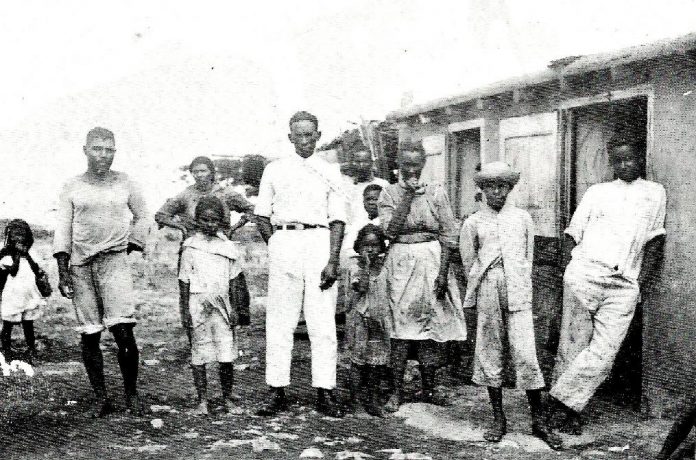

Records from 1820 indicate that Aruba had 331 persons deprived of freedom, of whom 157 were indigenous and 174 blacks; 15 blacks were born here, and 19 blacks had arrived as free men from abroad, bought and freed by generous natives.

Although the law did not allow indigenous people to be “catibo”, in practice it was different, and the legal situation of the indigenous people “brought” to our island from Guajira was not very clear. In an 1824 baptismal record, it is mentioned: “Jacobus, about 5 years old, Main Coast Indian of unknown parents.” In the same file, there are 32 names of other Guajira children who performed domestic chores or were considered “adoptive children.” These children did not receive a formal education since at that time there was no school, and despite being baptized, they were denied a “catholic burial”, mentioning only their first name, without their last names, as: “Jacobus de La Guajira”.

Testimonies passed from generation to generation assure us that these children were “stolen or captured in Guajira” and brought to our island.

They used to be called “catibo cora” or red slaves. We don’t know if the government counted them as “catibo”. The testimonies assure that Jan Hendrik Semeleer had three of these children from La Guajira, but he did not call them “catibo” but consider them as his own children.

Written testimonies by Pastor L. Jansen in the early 1900s say that Aruba treated its “catibo” as free people (see episode 108, about a slave from Argelia bought in Curacao and freed by prosecutor Alvarez in 1763 to live in Aruba).

When the children of the “catibo” were baptized, their godfather and godmother were the same as those of the adoptive family; this shows the good relationship that existed; while in Bonaire, only “another slave” could be “godfather or godmother of the baptism”, and Bonaire also did not allow marriage between “slaves” because “they had no civil rights.” Meanwhile, the records of Aruba show that in 1823, eight names of legitimate marriages of “catibo” were recorded; however, they were originally from Venezuela.

After the abolition, many “slaves” continued to live with the same family who owned them, as in the specific case of Beatrice Sierbol with the Figaroa family, whom they called “Ma Tichi.”

Before the emancipation, “a catibo”, or black slave, could buy their freedom for 400 florins, and also the children “of the catibo” were declared free.

Beginning in 1863, approximately one hundred new names of former slaves were registered for Aruba. Many of which have disappeared over time.

We can even recognize some of these surnames by the odd way they were formed using the Dutch language, like Knuppel (means club) or Goudstraet (means gold street) -etc. or other name compositions from Bonaire, like “Goedgedrag (means good behavior), –Braafhart (means good heart), –Scherptong (means sharp tongue), etc.

From those times, catibo, black slaves, and the common free people were mixed through marriage; therefore, “slavery” in Aruba covers a different story since although it existed legally, in terms of mistreatment and oppression, very little is known.

If you’re intrigued by Aruba`s native lifestyle and its cultural heritage do something outside of the tourist grid. Become one of the exclusive visitors of Etnia Nativa, a private museum/home where you will be able to touch and be touched by authentic Aruba heritage, a spectacle of native art, archaic as well as archaeological artifacts, lithic tools, colonial furniture, and other items of the island’s bygone era.

Etnia Nativa is, since 1994, the home of Anthony, our acclaimed columnist, artist craftsman, and island Piache, who guides and lectures you through his resplendent collection. Etnia Nativa is the only place that recreates and introduces you to an authentic glimpse into native cultural heritage. Something completely different for a change—a contemporary Native Aruba experience!

Appointment is required Whatsapp + 297 592 2702 or etnianativa03@gmail.com.