Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa is easy!

Article by Etnia Nativa call us 592 2702 and book your experience!

The narrative of Etnia Nativa — which means “Native Ethnicity” — underscores the importance of reclaiming Aruba’s cultural identity and heritage. Through this platform, it offers an authentic Indigenous perspective, educates the public, and inspires readers to adopt an island caretaker mindset.

In this episode, it explores how a crop like corn — originally domesticated in the Americas — has had a profound impact on agriculture, global food security, and cultural traditions across the world.

One of the most transformative outcomes of the Columbian Exchange, which began after Christopher Columbus’s voyages, was the global transfer of cash crops. This exchange radically reshaped global cuisine, economies, and patterns of population growth.

Originally from Mesoamerica, corn became one of the most significant crops introduced to the Old World. Its high yield and adaptability to diverse climates allowed it to thrive in Africa, Southern Europe, and Asia, where it quickly became a staple food. Beyond its agricultural value, corn also had a lasting cultural impact, becoming the foundation of traditional dishes—such as our funchi, a dense polenta-like staple.

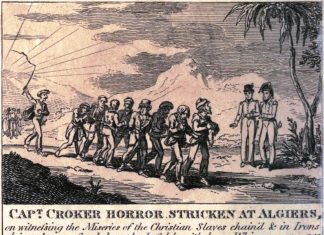

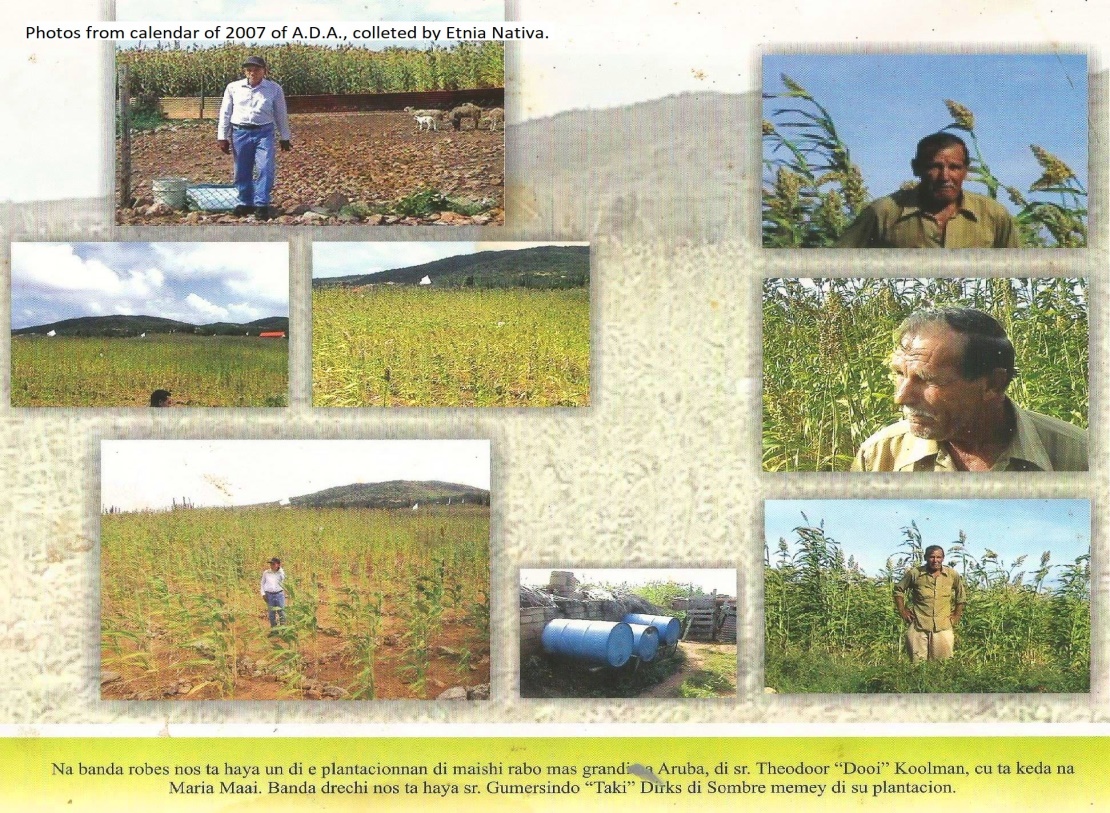

During the 19th century, as Aruba’s population grew and periods of regular rainfall became increasingly unpredictable, a corn-like plant known as sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) was introduced. Its cultivation gradually expanded, as farming persisted despite the challenges farmers faced in successfully growing other crops such as tobacco, cotton, peanuts, and cashews.

Sorghum and maize are closely related cereal grains. While they are different species—maize is Zea mays and sorghum is Sorghum bicolor—they share many botanical, agricultural, and cultural similarities. Sorghum, locally known as maishi rabo, belongs to the same grass family as maize. In their early stages of growth, plants like sugarcane, maize, and sorghum look so similar that they can easily be mistaken for one another by the untrained eye.

This visual similarity even influenced language. In the English-speaking Caribbean, maize was referred to as “large milho” and sorghum as “small milho.” In Papiamento, they are still known as maishi grandi (big corn) and maishi rabo (tail corn).

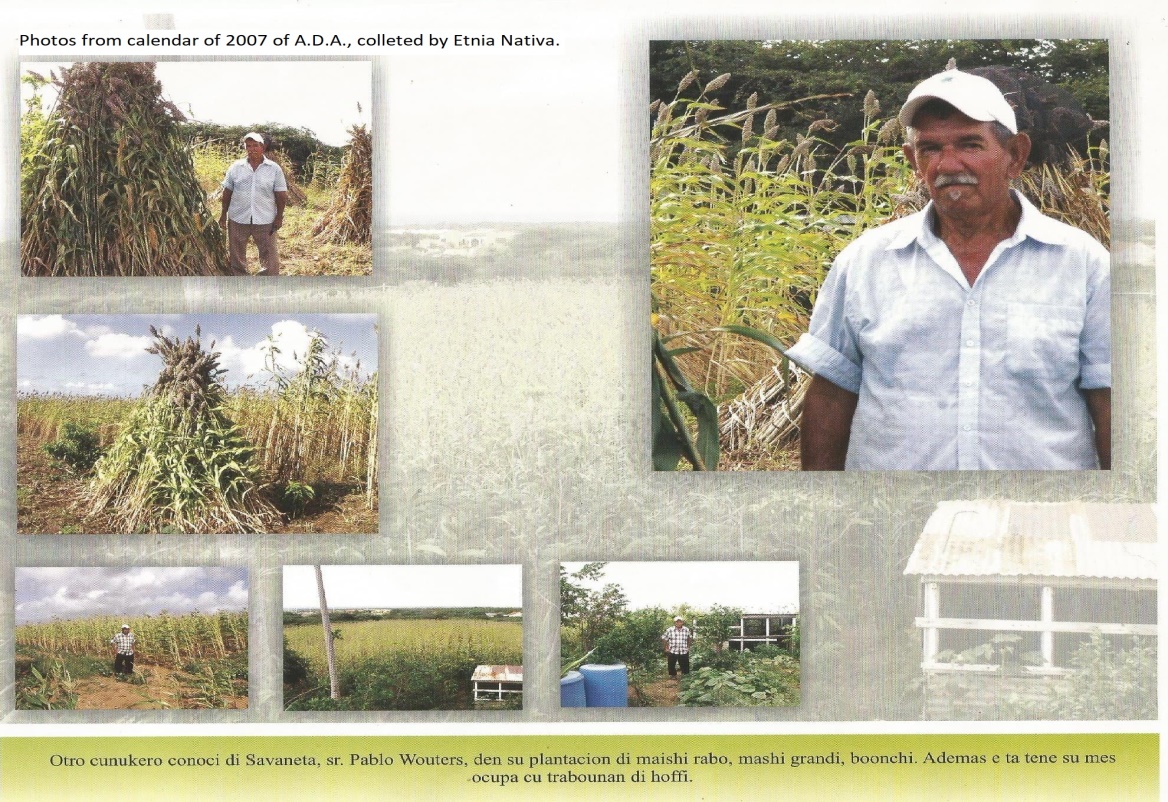

Sorghum cultivation became a traditional agricultural practice in Aruba. Farmers grew it on two types of plots: rich clay soil and nutrient-poor sandy soil. These were alternated strategically to reduce the risks posed by unpredictable rainfall. When heavy rains damaged crops on the clay-rich plots, the sandy fields often yielded better results—and vice versa.

Over time, Aruban farmers experimented with various imported varieties of sorghum, including Jerusalem corn and mild yellow corn. Eventually, a variety native to China proved the most resilient. It gradually replaced native corn on many cunucos (small agricultural plots), as it required less water and labor. This variety, nicknamed maishi di shete (“corn of seven”), earned its name because it could be harvested just seven weeks after sowing.

Priests were responsible for distributing the seeds, but cultivation remained a risky endeavor for even the most experienced Aruban farmers. Droughts could kill crops before they matured, and pests like beetles, worms, and ants frequently attacked them. Even when the plants survived, they sometimes developed an internal fluid caused by fluctuations in humidity. This fluid, known as maba, damaged the plant but could often be washed away by natural forces such as rainfall, wind, or sun.

Despite these challenges, Aruban farmers developed relatively advanced cultivation techniques. In prosperous years, they could produce two full harvests. Alongside corn, they also grew beans, squash, peanuts, cassava, and sweet potatoes. Fruits such as guava, soursop, and mangoes were cultivated as well—crops that reflect the enduring legacy of Native American agricultural traditions.

Today, the global diet remains deeply rooted in the crop exchanges between the New and Old Worlds. The spread of these plants transformed agriculture and shaped the cultures, economies, and livelihoods of millions. The legacy of the Columbian Exchange lives on in every bite. Imagine a pizza without tomatoes, a piña colada without pineapple, or a chocolate chip cookie without chocolate or vanilla.

If our ancestral stories stirred something within you, it’s time to unlock the hidden soul of the island. Discover Etnia Nativa — Aruba’s best-kept cultural secret. Just steps from the high-rise hotels, yet worlds away, this private sanctuary welcomes only the truly curious.

Step into a living museum — a sacred space where history, art, and identity converge, not for the masses, but for the mindful traveler.

Book your visit via Whats App +297 592 2702 or etnianativa03@gmail.com