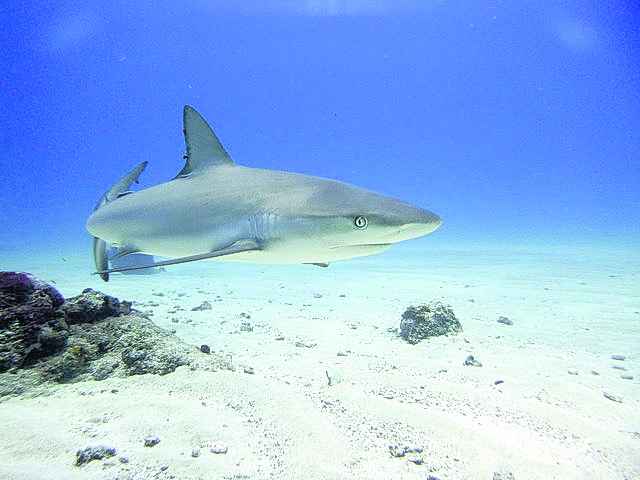

Wageningen Marine Research reported ten reef-associated shark species in the Dutch Caribbean in a published study as part of Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA)’s Save Our Sharks Project. The most common species are the nurse shark and the Caribbean reef shark. Overall, more sharks were observed in conservation areas than in unprotected areas, highlighting the importance of these zones in shark conservation.

More than 100 million sharks are killed each year as a result of fishing and shark finning activities, twice the rate at which they can reproduce. The demand for fins and other shark products has driven a number of species close to extinction. Sharks are especially vulnerable to overfishing and habitat degradation as they are late to mature and produce few young. The main threats to sharks in our waters are accidental bycatch, habitat degradation and the risk of a shark fin market developing, which would lead to targeted fishing of sharks.

We need healthy oceans and healthy oceans need sharks

Sharks keep our oceans healthy. These top predators remove sick or weak members of their prey populations. A decrease in number of sharks leads to a disturbed natural balance in the sea. This can affect the overall fish population, and good fish stocks are not only important for fishermen that depend on fishing but also for (dive) tourism and the local community.

Respect, not fear, sharks

Sharks are some of the most misunderstood species. For generations sharks had an undeserved bad reputation. People tend to see them as terrifying animals that pose a danger to everything that swims in the ocean, including humans. But we now know that is very far from the truth; these magnificent creatures are essential to healthy oceans and risks to humans are small.

DCNA’s Save Our Sharks Project

There is a lack of knowledge concerning the distribution and abundance of shark and ray species throughout the Dutch Caribbean. To combat this knowledge gap, from 2015-2018, DCNA ran the “Save our Sharks” (SOS) project for the Dutch Caribbean, funded by the Dutch Postcode Lottery. In this project DCNA collaborated with local fisherman and scientists and aimed to build popular support for shark and ray conservation amongst the local community, as well as increasing knowledge about shark and ray species within the region by conducting a number of research projects.

Shark Research

A recently published study by Wageningen Marine Research as part of DCNA’s SOS Project established a baseline for current shark diversity, distribution, abundance, spatial behaviour and population structure for inshore reefs around the Dutch Caribbean islands.

There were two methods used by the researchers to study sharks. One method used Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) which used a device consisting of two cameras set in front of a baited feed bag. The idea is that as sharks come near the bait bag to feed, video footage can be collected to identify and count local shark populations. The other method was acoustic telemetry to track sharks. In this method, a small acoustic tracking device is implanted within the shark. Acoustic receivers are installed at specific locations, and whenever sharks with these transmitters travel near the receiver (within a range of 450 to 850 metres) they are recorded.

The first studies using BRUV were conducted on Saba, Saba Bank and St. Eustatius to better understand the local population of sharks and rays and their relative abundances, and were funded by the Dutch Government. Starting in 2015, as part of the SOS project, additional studies were conducted to include the waters around Bonaire, Curaçao and Sint Maarten. In 2017 a BRUV survey was done at Aruba, financed by Global Finprint.

In addition, as part of the SOS project, acoustic telemetry was also used to better understand the movements of sharks, habitat use, migration and connectivity between islands. The telemetry study tracked two shark species, Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi) and nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) around Saba (from 2014) and then around Saba Bank, Sint Maarten and Sint Eustatius (from 2015).

Findings

In BRUVs deployed around Sint Maarten, Curaçao and Bonaire the most common detected shark species were Caribbean reef shark, with Sint Maarten also frequently showing nurse sharks. Overall, more sharks were observed in marine parks or areas of conservation than in unprotected areas, highlighting the importance of these zones in shark conservation. Furthermore, when comparing the BRUV surveys from Sint Maarten, Curaçao and Bonaire to previous BRUV studies from Aruba, Saba, Sint Eustatius and Saba Bank, it showed that the Aruba survey had the largest shark diversity (8 species) and the Bonaire survey the lowest (2 species). The Saba survey documented 5 shark species, Saba bank had 4 shark species with Curaçao, Sint Eustatius and Sint Maarten each registering 3 shark species. There was an additional BRUV submarine test at 300 metres deep off Curaçao which found an additional shark species (Cuban dogfish). In total, at least 10 shark species were seen within the Dutch Caribbean in the different BRUV surveys.

The acoustic telemetry studies demonstrated that both the Caribbean reef shark and nurse shark have small home ranges and strong site fidelity. Large crossings between areas were rare, and found for two Caribbean reef sharks and one nurse shark which travelled between Saba and Saba bank. The two Caribbean reef sharks made short directed journeys back and forth, whereas the nurse shark after two years absence showed up at the Saba Bank before returning to Saba. One nurse shark from another study on the US Virgin Islands was detected in the network on the Saba Bank, a distance of at least 160 kilometres.

Importance of Protected Areas

Both the BRUV and acoustic telemetry studies showed higher presence of reef associated sharks within the conservation zones, along with high site fidelity and small home ranges. Furthermore, as some longer distance movements were also documented, interconnectivity between these areas is just beginning to be understood. The ongoing study on acoustic telemetry (funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV)) will yield more data on this. Therefore, not only are local marine parks crucial for the conservation efforts of sharks and rays, but larger conservation networks, such as the Yarari Marine Mammal and Shark Sanctuary which compromises all the waters of Bonaire, Saba and Sint Eustatius, are vital to protect entire populations.